"We Got Schools Wrong"

Health experts discuss the mistakes made with school closures

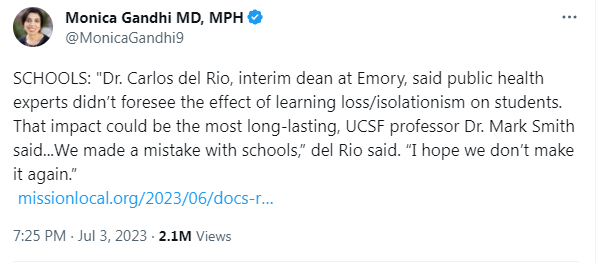

Earlier this week, Monica Gandhi shared an excerpt from an article in Mission Local (an independent news site based in the Mission District of San Francisco), in which Dr. Carlos del Rio is quoted saying that school closures were a mistake that he hopes we won’t make again. The excerpt also included the following sentence: “Dr. Carlos del Rio, interim dean at Emory University School of Medicine, said public health experts didn’t foresee the effect of learning loss and isolationism on students.”

Many people were glad to see Dr. del Rio admit that school closures were a mistake, but stunned by the idea that the harms weren’t predicted by public health experts. Personally, I was a bit skeptical of this claim.

I have interacted with Dr. del Rio many times on Twitter during the pandemic, partly because he is local to me here in Atlanta, and he works at my alma mater, Emory University. While we don’t always see eye to eye, something didn’t seem right about these comments he supposedly made. So I tracked down the video of the actual UCSF Grand Rounds that this article was written based on, in which Bob Wachter spoke with Carlos del Rio, Katelyn Jetelina, and Mark D. Smith.

What I found was that the article was a very rough approximation of what the participants said. Even the statements in the article that are in quotation marks are NOT direct quotes from the video. It is simply poor journalism, unfortunately, which led to this viral tweet. Nobody in the video ever said that public health didn’t know school closures would be harmful.

What Was Actually Said…

In the video, Bob Wachter asked the three participants about school closures:

“…if we did get it wrong, was it because we overestimated the risk, or we underestimated the downsides of keeping kids out of school, like, what the educational attainment downsides were, what the mental health downsides were, what the downsides for parents were, all those sort of things? Sort of which part of it did we get wrong, if we got any of it wrong?”

None of the participants replied that we underestimated or didn’t foresee the harms to students of school closures. The responses from epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina and Mark Smith, a medical doctor, both stated unequivocally that experts believed Covid would be more dangerous for children than it turned out to be. Dr. del Rio said he agreed with Dr. Jetelina, and added that public health forgot how important schools are to parents and the economy.

Dr. Katelyn Jetelina

Katelyn Jetelina answered first, and described how experts assumed Covid would be “very bad for young kids.” If this is true, it means that instead of “following the science,” experts ignored all the early data from China, Italy, and the Diamond Princess showing the severe age-gradient with Covid-19, and how it was not a significant threat to most children.

She also said that “we thought, and we were wrong, that schools would accelerate transmission in a community.” However, by summer 2020, there was ample data showing this wasn’t true, again showing that U.S. public health did not “follow the science” when it came to kids and Covid. Many countries in Europe successfully reopened schools in Spring 2020, Sweden famously never closed their lower schools, and New York City had child care centers that successfully stayed open during Spring 2020. Despite this wealth of evidence, many U.S. schools remained closed much longer, with public health warnings about concerns of transmission within and from schools.

Earlier in the discussion, Dr. Jetelina mentioned that as an epidemiologist, she was “very uncomfortable” with schools reopening in August/September 2020 in Texas, where she lived at the time, but then she reluctantly admitted that “looking back, I think it was the right call.” She added that she felt like reopening schools was a difficult decision prior to vaccines, asking teachers to go on the front lines. While I understand that sentiment, I would push back on Dr. Jetelina and remind her that we asked many other professions to continue working in person in 2020 to keep society functioning. Why was it difficult to ask teachers to work in-person, but not doctors, law enforcement officers, or workers at Amazon warehouses and local grocery stores?

Dr. Carlos del Rio

Dr. del Rio stated he agreed with Dr. Jetelina. He said we needed to close schools initially “…for a second. But then we kept them closed for way too long.” I am not sure I agree that there was ever a need to close schools, but I understand March 2020 was filled with a lot of difficult decisions. I do think we should have reopened in April, and I wish he would have said that. I’d be curious if he believes that, in hindsight.

In addition, Dr. del Rio spoke about advising both Atlanta Public Schools (APS) and a local private school on reopening. Atlanta Public Schools had a phased re-opening from January 25 through February 16, 2021, with protocols such as test-to-stay (after an exposure) and voluntary surveillance testing through a private company. Fulton County Schools, which surrounds APS, returned to in-person in October 2020, and schools in suburban Cobb and Gwinnett County also re-opened in Fall 2020. Students in neighboring DeKalb County Schools (where Emory University and the CDC are located) didn’t return until March 2021.

Dr. del Rio also added that public health forgot how harmful school closures would be for parents and for the economy, explaining, “you can’t go to work if you — you can’t work at home or work, period — if you have kids around in the house, right?” It was nice to see some recognition that one of the important functions of schools is to keep society functioning, but I do wish he’d recognized that public health also seemingly prioritized avoiding Covid over everything else — the economy, normal social functioning, and the mental health and academic futures of young people.

Dr. Mark Smith

Finally, Dr. Mark Smith said that he doesn’t want to “second guess” some of the difficult decisions officials made about schools, and echoed Jetelina’s comments about severity in children, saying that “there was every reason to believe that this virus would be particularly bad for kids.” Again, this simply isn’t true, and wasn’t true at the time. All the early data showed that children were at the lowest risk of severe disease from SARS-CoV-2 and most of the severe cases were among seniors and the elderly.

Dr. Smith went on to discuss how the experience during Covid was very different for those who were able to work from home, versus those whose livelihoods depended on jobs and businesses that required being in person. This is a key point that I think was underappreciated by public health, the media, and many Americans. He also emphasized the seriousness of the impact of school closures, saying:

“There’s no question that aspects of the economy and people’s personal lives have been devastated. There’s also no question, this may — the decrease in educational attainment that we’re only now beginning to measure — may be the longest COVID of all, if you will. It may be the thing that has the most lasting impact on the life chances and opportunities of that generation of kids that went through that shutdown.”

My Closing Thoughts

None of these people are in positions of authority to set policy on schools in the U.S., which were mostly decided by public health directors, politicians, and school board members. But they are influencers in the area of public health, and they had influence both at the local and national level, along with many other doctors and scientists. It is nice to see them acknowledge some things that we got wrong about kids and Covid; but at the same time, it’s very discouraging to see how they embraced the incorrect theories that kids were at significant risk of severe Covid outcomes and that schools would lead to Covid spread in the community, despite lots of early data showing that neither of those things were true.

We were told public health was following the science, but I think in many cases, they were driven by their own fears. Public health went all in on avoiding Covid harms, to the detriment of everything else, especially when it came to schools. They failed to do a proper risk-benefit analysis of the recommendations they were making. Many people were begging officials to consider some of the second- and third-order effects of school closures, but we were dismissed as Covid deniers, racists, and grandma killers. In reality, we were evaluating evidence on kids and Covid and were concerned about the obvious harms that were occurring as a result of extended school closures in the U.S.

I’ll end by saying that I agree with Dr. del Rio in that I “hope we don’t make this mistake again.” I think the best way to do that is to get more experts to acknowledge that school closures in the U.S. were a complete failure of public health.

Video & Transcript

The following is a transcript from the UCSF Final Covid-19 Grand Rounds, specifically the portion of the discussion about schools and the economy

28:36 WACHTER: I think even among people who are clear thinking about how bad it was in 2020, there’s a lot of sentiment that we got the schools wrong. And Katelyn, you mentioned, “I wouldn’t take my kids out of preschool” [if cases started increasing again - approx. 23:40]. Maybe Katelyn, to start, do you think we got the schools wrong? What did we learn about the schools?

28:56 JETELINA: So I was in Texas during the pandemic, and as an epidemiologist, and we actually started schools very early. It was like, it was August, September of 2020. At the time, I was very uncomfortable as an epidemiologist, but it was pushed forward. And, you know, looking back, I think it was the right call. I think that we could’ve prepared schools and prepared teachers far better with ventilation, with contact tracing, with resources, that just weren’t utilized in the time of early 2020.

I think the really hard thing that I had in fall of 2020 was that we just didn’t have vaccines yet. It was hard for me to ask teachers to go, you know, even if they’re, you know, over 65, under 65, it was a very random disease before any immunity. And to ask someone to go on the front line, that was a hard decision for me to make before we had any levels of protection for them. And so, I don’t know.

30:15 WACHTER: Yeah. It really is a hard one. I scratch my head about it too. But do you think a lesson, as people talk about the schools, and we quote, “Got the schools wrong.” First of all, it’s an interesting question in general, but second of all, did we, if we did get it wrong, was it because we overestimated the risk, or we underestimated the downsides of keeping kids out of school, like, what the educational attainment downsides were, what the mental health downsides were, what the downsides for parents were, all those sort of things? Sort of which part of it did we get wrong, if we got any of it wrong?

30:47 JETELINA: That’s a really, I think that’s a really good question. The one thing we got wrong was, well, for one, almost every virus is usually very bad for young kids. And this one just wasn’t. It was very weird. And that is abnormal. So I will say that.

The second thing is we thought, and we were wrong, that schools would accelerate transmission in a community, but rather they just reflected the community transmission. They didn’t become these vectors of really high transmission. I was surprised about that.

31:30 WACHTER: Why not? You would think they would’ve been.

JETELINA: I thought they would’ve been too. I think we have a lot to learn about that. And was it because of SARS-CoV-2? Was it because it was just literally everywhere anyways? I’m not sure. I do know, you know, public health people do recognize whole health, the value of mental health, a safety net, meals at schools, and that was very much a part of the conversation in Texas in early 2020 as well. So it was, a lot of people had to make very hard decisions at that time, and I don’t empathize* anyone in that decision making effort. (*I believe she meant envy, not empathize.)

32:17 WACHTER: Carlos, what do you, what did, first, let’s start with did we get the schools wrong? And if so, what would we, what’s that lesson learned?

32:22 DEL RIO: You know, I agree with Katelyn. I think, you know, initially we closed schools. It was a necessary move for a second. But then we kept them closed for way too long. And that has been bad. And in some places kept schools closed forever, right? They basically, I’m hearing now, many school districts having trouble getting students to come back. This has been really bad for our kids, for parents.

And we have to remember that one of the key ways to reactivate the economy was to open schools again. It’s very important for parents. You can’t go to work if you — you can’t work at home or work, period — if you have kids around in the house, right? If you have to be the teacher and the mother, you can’t do work. You know, you can’t be, no matter what happens. So we forgot that.

In schools, I worked with some schools here in Atlanta, one of them a private school, Paideia School, one of them, you know, the Atlanta public schools. And we did a lot of testing, and we kept schools open as much as possible. And yes, we did it before there were vaccines. And once there were vaccines, we prioritized the teachers. And we didn’t see outbreak. We were able to really control transmission, and send people, you know, home when they were infected, and really prevent the school from being a site of infection. And that was very important for mental health of the kids.

So, my message is that one of the things we got wrong is the schools. And we hope we don’t make this mistake again when we have another pandemic.

33:45 WACHTER: Okay, let me turn to Mark as the, I think only MBA in our group here. One other question, I think there’s less certainty when you hear people say it is, we got the balance of the economy and public health wrong. What do you think?

34:05 SMITH: I’m loathe to second guess from the safety of two thousand — the relative safety of 2023 — some of the hard decisions that people had to make, like in schools, in part because, let’s remember that we didn’t — there was every reason to believe that this virus would be particularly bad for kids. There was every reason to believe things that turned out not to be.

So remember, we were wiping down our groceries, and we wouldn’t touch our face because the virus system, I mean, we didn’t know. Having said that, it does strike me that the ferocity with which some people opposed, what seemed to some, reasonable public health restrictions depended in part on whether you made your livelihood, whether you could do your livelihood at home versus wherever else.

So last week, there was a study published about how likely various occupations were to be working from home. And like software engineers were at the top, and butchers were at the bottom.

And so if you had saved all your life to start a restaurant, and you bought furniture and hired staff and opened your doors in March of 2020, and then it all went to hell, I get how your perspective on the shutdown of the economy, and whether or not we, quote, “got the balance right,” would be a little bit different from someone who could set up their Zoom and do what they do as we’re doing this now.

So you’ll remember the early days when it became immediately apparent that certain ethnicities were harder hit, were sicker, were hospitalized more, were dying, and the explanation in lay press was that they had too many preexisting conditions, right? And the problems with that were, first, no one said, “Well, gee, why is it that Black people have more hypertension, diabetes, Latino people?”

But the second thing was it wasn’t entirely true, that the preexisting condition was that you worked in a meat packing plant, or that you drove the bus, or that you had a multi-generational household. And so the impact of the epidemic and the impact of the restrictions that were imposed to try to control the epidemic under very difficult circumstances hit people quite differently, depending on where you are in the economy.

So it’s part of why I’m punting on the question, ’cause I think it depends a little bit on where you were, and people were making hard decisions under conditions of great uncertainty. There’s no question that aspects of the economy and people’s personal lives have been devastated.

There’s also no question, this may — the decrease in educational attainment that we’re only now beginning to measure — may be the longest COVID of all, if you will. It may be the thing that has the most lasting impact on the life chances and opportunities of that generation of kids that went through that shutdown. So that’s the point.

37:06 WACHTER: Yeah.

37:07 DEL RIO: So Bob, I would say though that an important message is I think in public health, we make the mistake of letting the population say, “It’s either public health or the economy. It’s public health versus the economy.” When the reality is we need a strong, a good public health in order for the economy to be successful. A healthy population is important for the economy to be successful. So we needed to really get the message.

And I think in public health, we didn’t get the message right of telling people, “Look, our goal is to get the economy going. This is the public health and this is how public health is doing. We’re not shutting the economy, we’re actually gonna do the adjustments to get the economy right.” And this, again, it was all about not telling people necessarily what not to do, it was telling people how to do things in order to continue working. And there were ways to do that.

And I think we made the mistake of saying no as opposed to saying, “This is what you need to do.” And I go back to my roots in HIV. You know, it’s harm reduction. It’s not about telling people you shouldn’t have sex. It’s about what to tell them to decrease their risk.

CORRECTION: Originally, this article referred to Dr. Mark Smith as Dr. Mark Sims in a few instances. I apologize for the error.

It's good to see Del Rio talking about harm reduction rather than edicts and prohibition. But did any public health people in the U.S. criticize the edicts and prohibition approach during 2020 and 2021? Hand-wringing on Zoom 3 years after the mistakes were made is terribly inadequate.

Also, it's not only that public health didn't look at the evidence from classrooms opening back up in Europe in spring 2020. I believe Kelley's noted that Wyoming and Montana reopened classrooms before school let out that June. Although, it seems that was on a very limited basis. See this, for example: https://oilcity.news/wyoming/2020/04/28/wyoming-schools-to-remain-closed-through-may-15th/