Confusion and chaos in mpox reporting

What you need to know to make sense of the recent outbreak

I wasn’t planning to write about mpox initially, but there has been so much confusion and bad reporting that I thought it would be helpful to clarify some common misunderstandings. This should help alleviate fears for some people who are anxious about the new outbreak. But if you’re assuming it’s just like the 2022 outbreak all over again, it’s not — it’s a little more complicated. However, the risk to children in the US and other Western nations has been grossly overstated.

What’s all the talk about clades?

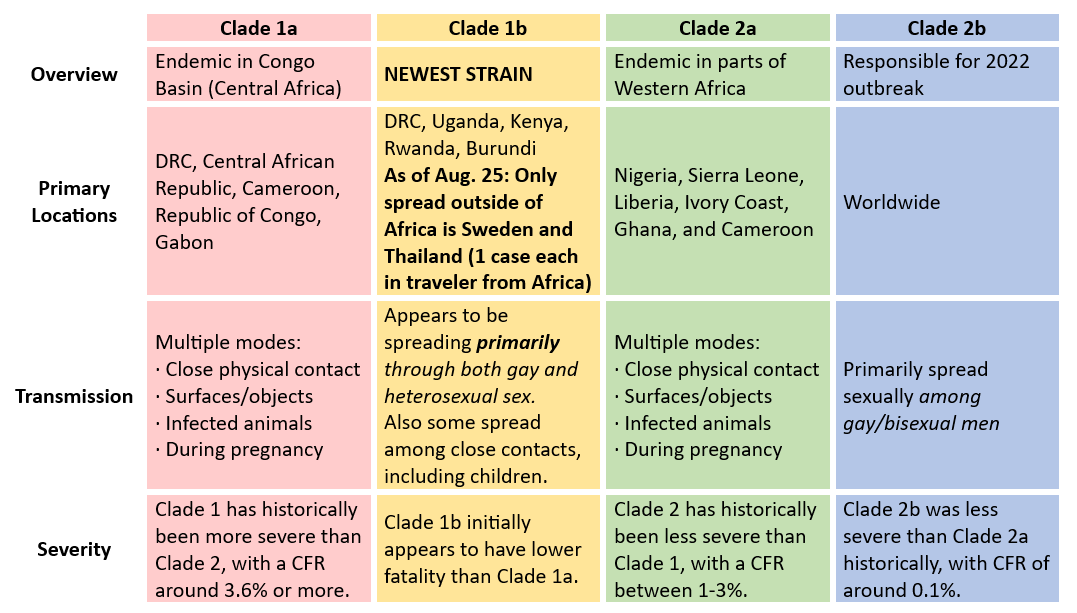

The monkeypox virus (MPVX), which causes the disease now known as mpox, has been endemic to central and western Africa for decades. Two versions, or clades, of the virus have been spreading in Africa for many years: clade 1, previously known as the Congo Basin clade, and clade 2, previously known as the West Africa clade1. Of these endemic clades, clade 1 has historically been more severe than clade 2.2

In 2022, a variant of clade 2 known as clade 2b (IIb) began spreading globally, primarily through sexual contact among gay and bisexual men (also referred to as MSM, “men who have sex with men”). That outbreak spread quickly, then peaked and numbers have been low since, due to some combination immunity from infection and vaccination, as well as awareness and behavior changes. Clade 2b also had a lower fatality rate globally than previously seen with clade 2a in Africa.

The current 2024 outbreak is being driven by clade 1 — both the endemic 1a variety, as well as a new variant known as clade 1b.

Clade 1b (Ib) was discovered in Africa in late 2023 and began spreading quickly in the eastern portion of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and neighboring countries, primarily through sexual contact — but not only among men. This version has also been affecting women, with spread seen among sex workers.3 It’s still early to know much with certainty about this newest strain, but reports that clade 1b is the “deadliest yet” are unfounded.

An early outbreak of 1b in the South Kivu region of DRC had a CFR (case fatality rate) of 0.6% among ~3000 cases.4 Clade 1b has also spread among children and young people in the country of Burundi, which borders South Kivu, but no fatalities have been reported yet from the outbreak in Burundi.5

According to the European CDC, “preliminary data show that infections by clade Ib virus concern mostly the adult population, whereas infections by clade Ia concern mostly children.”6

While the outbreak in Africa involves both clade 1a and 1b, the WHO seems to be more concerned about clade 1b spreading to other countries. I suspect this because sexual networks are larger and more geographically diverse, giving more opportunity for spread outside of Africa than clade 1a, which spreads more from infected animals and within families.

More Details about Transmission & Severity

More information about the four varieties of mpox are detailed below. The two that are driving the current outbreak are clade 1a and 1b. However, clade 2 is still circulating in endemic parts of Africa, and clade 2b is still being found in countries all over the world — but in much smaller numbers than during the 2022 outbreak. When you hear about a suspected case of mpox in the news, it’s important to wait and find out what clade it is. We shouldn’t be surprised to see sporadic reports of clade 2b, particularly among MSM.

As of August 25, 2024, we only have two confirmed reports of clade 1 outside of Africa (both clade 1b) — in Sweden and in Thailand. Both cases were in travelers who recently came from affected areas in Africa. Other news reports about suspected cases turned out to be clade 2b or not mpox at all.

In countries in Africa where mpox is endemic, it has been known to spread through a variety of methods, both from animals and infected people to their close contacts7:

Close physical contact: The virus spreads via skin-to-skin contact with sores, through saliva and other bodily fluids, during sex or other intimate interactions, and from pregnant mothers to their unborn babies.

NOTE: Some sources list “talking or breathing close” as potential avenues for transmission, but it is thought that cases of true respiratory spread are rare. The CDC specifies prolonged close contact for these avenues, which would likely also include some aspect of touch or droplet spread.

Surfaces/objects: Shared items such as bedding, clothes, dishes, etc. may spread the disease if contaminated by an infected person.

Infected animals: In areas of Central and Western Africa, small wild animals carry the MPVX virus, and it can spread through close contact with these animals or their bodily fluids or feces, or by hunting and eating these animals.

During pregnancy: An infected mother may pass the virus on to her unborn baby.

While it is still early, and testing and case reporting in African countries is imprecise, it appears that the new clade 1b may have lower severity than the endemic clade 1a, just like clade 2b had lower severity than the endemic clade 2a. Many reports have claimed that this new variant is known to be the most deadly, but they seem to be conflating the new clade 1b with the endemic clade 1a.

Why did the WHO declare an emergency over mpox?

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) to alert countries around the world about the increased spread in Africa. They were concerned about the new 1b clade spreading via sexual networks outside of Africa, much like clade 2b did in 2022. They also wanted to draw international resources (public health response teams, funding, and vaccines) to Africa to help curtail the spread there. DRC has been in political turmoil, and needs assistance in responding to the outbreak.

What about children? Should we worry about schools?

Endemic versions of mpox have often caused outbreaks among families and children — this is not new. The clade 2b outbreak in 2022 did not affect many children, but fears about spread in schools and colleges were not uncommon on social media and even in mainstream media based on claims by some medical and public health in the US. We’re already seeing a lot of fear mongering about this new variant affecting more children. While children have made up the majority of cases and deaths during the current outbreak in Africa, the majority of this is believed to be spread of the endemic clade 1a that has historically affected children and families — not the new clade 1b.

The Burundi outbreak of clade 1b has impacted children, but there have been no fatalities reported. Typically, children have had the highest fatality rates of the endemic strains of mpox, but we do not yet have data about infection or fatality rates for the new clade 1b among children. At this point, there is no reason to fear school closures or spread of mpox in schools outside of Africa.

Why would spread in Africa be different than the US?

To understand the increased risk of spread among children and families in central Africa compared to the risk in the US, you must recognize how different the situation is in Africa. Children in central Africa are often malnourished and sick with other diseases, making them more vulnerable. In addition, their sanitation systems and hygiene practices are not like in the US, and many families live in overcrowded housing and shelters, and they share beds and other personal items. Conflict/war in DRC has also contributed to deteriorating conditions in the area.

In addition, the education and healthcare systems in central Africa are vastly different than the US, so they may not have appropriate information about how to prevent the spread of mpox, and their hospitals are not as equipped to isolate and treat those infected. In addition, many children and young people are exposed to mpox when hunting, skinning, or cooking wild animals in central Africa that carry the disease. These factors all lead to vastly more opportunities for mpox to spread among children and families in central Africa than in the West.

What should we do?

For now, helping to slow the outbreak in Africa will help protect other countries around the world. Some countries are donating vaccines, some are sending teams or other resources to help educate and train people on the ground in Africa. It’s also important to increase awareness about transmission and symptoms to those traveling to or from Africa, and respond quickly if cases are imported or found to be spreading in other countries outside the affected region. Other than that, the risk in the US and other Western nations remains low at this time.

In the US, the CDC is continuing to recommend mpox vaccination for gay/bisexual men at risk of contracting the disease. Some countries, like Sweden, are also beginning to vaccinate aid workers and healthcare workers who will be working in locations with active outbreaks.

One final thought…

There has been a great deal of fear mongering since the WHO announced the PHEIC along the lines of “mpox is back, it’s more deadly than ever, and this time it’s coming for your kids!”

This is irresponsible and inaccurate messaging. Many people have blamed public health for these exaggerations, assuming it’s propaganda from the WHO. After Covid, I absolutely understand this tendency to blame public health for exaggerating the risk. However, in the case of mpox, I have actually found official messaging from health agencies to be more factual and reassuring, while the media has been talking to “experts” who are getting the data wrong and exaggerating the risk to countries outside of Africa from the current outbreak. Please be sure you’re getting your information from reliable sources.

Thank you for this super helpful discussion. I’ve been confused by the different clades and you help me to compartmentalize them in my mind.

Thank you so much for this concise overview, it's a great service!