Unrealistic Long Covid Estimates

Flawed studies suggest up to 80% get Long Covid

Before Covid, I had a much higher opinion of most academics. Over the past few years, my eyes have been opened about the state of academia. I’ve been challenging study findings throughout the past few years, but some Long Covid studies I recently came across still shocked me at the way they misinterpret the data in a way that seriously biases their results.

There have been a multitude of studies on Long Covid symptoms and prevalence. The data is all over the map, because the underlying subjects, definitions, and time periods are all quite different. One one hand, there are studies that only include those hospitalized for Covid, while others include anyone who even thinks they had Covid, no testing required. In addition, Long Covid is often defined broadly to include common symptoms such as cough, fatigue, anxiety, muscle aches, etc. And there’s no set requirement for how long after infection these symptoms much exist. Study methodologies are also often weak, lacking control groups and relying on surveys with poor response rates. As a result, it’s very hard to get any sort of consistent estimates about how many people have Long Covid. But that doesn’t stop researchers from trying!

Long Covid Affects up to 80% of “Covid Survivors”?!?

Recently I came across two different sources that said Long Covid could affect up to 80% of “Covid survivors”— one was an article in Fortune Magazine by Paige McGlauflin, and one in a new Long Covid study from George Washington University, which was just published in a CDC journal and shared by Eric Topol on Twitter.

George Washington University Long Covid Study

This recent study found that 36% of George Washington students and faculty who had Covid developed Long Covid, an implausibly high number. However, they support their findings by explaining that it’s within the 10-80% estimate from other studies. But what happens when the cited estimate comes from a flawed meta-analysis? Flawed studies lend credibility to other flawed studies in an endless cycle of bad science.

Fortune Magazine

In December, I contacted the author of the Fortune Magazine article to find her source for the 80% claim, which turned out to be an earlier Fortune article by Erin Prater. Erin’s article linked the 80% number to a systematic review of Long Covid studies.

I initially assumed the George Washington study was also referencing that same systematic review, but it turns out, they got that number from a different meta-analysis of Long Covid studies. Obviously 80% is a patently absurd estimate for Long Covid prevalence, and both papers turned out to have very basic and obvious flaws in incorporating the underlying research. How exactly does this stuff get published?!? Peer review is obviously a joke.

A Flawed Systematic Review

First is the review paper cited in Fortune Magazine. This paper published in the International Journal of Clinical Practice in October 2021 included “25 observational studies with moderate to high methodological quality” and found that “the frequency of long COVID-19 ranged from 4.7% to 80%.” This is an absurdly wide range, and of course, the 80% is what has the impact. The timing for follow-up was as little as 3 weeks after acute phase or hospital discharge. So basically, this study tells us nothing.

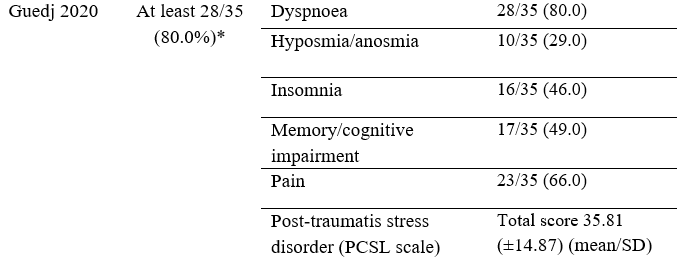

The authors provided a table of each underlying study, and the prevalence of Long Covid obtained from each study. This is where it gets really funny. Or is it sad? I don’t know. I found the details for the study that they said showed an “Overall frequency of long COVID” of 80%, based on “the most prevalent persistent symptom,” which was dyspnoea (shortness of breath). That sounds pretty shocking, no? So I took a look at the underlying Long Covid study by Guedj et. al. to see if I could find the issue.

Here’s a hint — the paper is titled “18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID.” That’s right, it’s a study of Long Covid patients. The methods section begins “PET scans of 35 patients with long COVID were compared…” I actually am fairly amused that the authors of the review only listed it as 80% based on their choice to use the prevalence of the most common symptom for several of the studies (that’s what the * refers to after the 80%). This study obviously can’t be used to estimate prevalence of Long Covid.

Here are details from other studies included that showed a prevalence of 60% or more:

Carvalho-Scheneider (listed as 68%, actually 66%) - Patients tested at a French hospital in Spring 2020.

Halpin (64%) - Hospitalized patients from Spring 2020 in the UK. 32% were treated in the ICU.

Huang (76%) - Hospitalized patients from Wuhan, Jan-May 2020.

Jacobs (72.7%) - Hospitalized patients from New Jersey, Spring 2020 with a median age of 57 and median hospital stay of 7 days.

Liang (62%) - Hospitalized patients from Wuhan, mostly health care workers.

Rosales-Castillo (62.5%) - Hospitalized patients in Spain, with an average age of 60 and an average hospital stay of 11 days.

Tarazona-Fernandez (60% with 2-3 symptoms) - Like the Guedj study, this was also a study exclusively of Long Covid patients in Peru. “43 evaluations were carried out on patients … continuing to present clinical manifestations similar to those they had during the first to second week of symptomatic disease.”

I contacted the corresponding author for the systematic review in mid-December to point out the issue with the Guedj study and their finding of 80% prevalence, but I did not receive a response. I’ve sent a follow-up email and will update if l hear back.

A Flawed Meta-Analysis

After finding such an obvious flaw in the previous systematic review last month, I wasn’t sure what to expect from this study showing an 80% Long Covid rate that was cited in the recent study. First I had to track down which of the many studies referenced by the George Washington University study included the 80% number:

“Regardless of initial symptoms, nearly 36% of COVID-19 survivors in this study reported experiencing symptoms consistent with long COVID. That result is within ranges found in other studies reporting a prevalence of long COVID of anywhere from 10% to 80% among COVID-19 survivors (3–5,7,21,29–31).”

I tracked it down to the paper shown below, a systematic review and meta-analysis of Long Covid published in the journal Scientific Reports, describing more than 50 long-term effects of Covid by Lopez-Leon et. al. The 15 underlying studies in this paper “defined long-COVID as ranging from 14 to 110 days post-viral infection.” Based on their analysis, and the study authors “estimated that 80% of the infected patients with SARS-CoV-2 developed one or more long-term symptoms.”

One of the supplements of this paper is a collection of forest plots showing long-term effects of Covid grouped by symptom type, with the first plot being simply for studies that showed one or more symptom. These seven studies range from 50 to 94% with one or more Long Covid symptom, with an overall estimate of 80% (95% CI 65–92) Covid patients having long-term symptoms based on their meta-analysis. Honestly, how could any serious researcher believe this?!?

I went straight to the study that showed the highest rate of 94% — an MMWR by Tenforde et. al. — and I searched for 94%. Any guesses what I found? “Among the 292 remaining patient respondents, 274 (94%) reported one or more symptoms at testing and were included in this data analysis.” That’s right — 94% were symptomatic during the acute phase of the illness. This is obviously not an estimate of Long Covid. The researchers doing the meta-analysis just grabbed the wrong number from this study. The actual findings of the MMWR were that “35% had not returned to their usual state of health when interviewed 2–3 weeks after testing.”

Here are the other studies included in that meta-analysis with some comments about their accuracy and applicability:

Carfi (87%) - Hospitalized patients from Italy in Spring 2020, and almost 3/4 had pneumonia while hospitalized. Most common symptoms were fatigue and shortness of breath.

Carvalho-Schneider (66%) - Patients tested at a French hospital in Spring 2020. “Up to 2 months after symptom onset, two thirds of adults with noncritical COVID-19 had complaints, mainly anosmia/ageusia, dyspnoea or asthenia.”

Galvan-Tejada (84%) - This was a case-control study. While 84% of the infected had at least one symptom, 35% of the control group also had at least one symptom! That seems to have been ignored by the meta-analysis authors.

Kamal (89%) - No mention of how long after initial infection. The paper just vaguely references “after the last negative PCR.” Most common symptom was fatigue in 72.8%.

Mandal (72%) - Hospitalized patients with an average age of 60 years old and a median hospital stay of nearly a week.

Xiong (50%) - Hospitalized patients from Wuhan prior to March 2020.

I have contacted the author of this study, and will update this article if I hear back.

I hope to dig into studies like this more often, because I suspect these kind of mistakes, which have the potential to grossly influence the results, are not uncommon. And once a paper like this gets published, it is cited in news articles, misleading the general public, as well as by other studies to support the credibility of their results. It would be nice if these kind of egregious errors were caught during the peer review process so that flawed studies don’t get published, but I don’t have a lot of faith in that process.

Reputations are being made and burnished codifying this. Let alone the 1.15 billion research money avail per NIH to study it: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-022-00846-2